Search the Blog

Categories

- Books & Reading

- Broadband Buzz

- Census

- Education & Training

- General

- Grants

- Information Resources

- Library Management

- Nebraska Center for the Book

- Nebraska Memories

- Now hiring @ your library

- Preservation

- Pretty Sweet Tech

- Programming

- Public Library Boards of Trustees

- Public Relations

- Talking Book & Braille Service (TBBS)

- Technology

- Uncategorized

- What's Up Doc / Govdocs

- Youth Services

Archives

Subscribe

Tag Archives: Friday Reads

Friday Reads: I.M.: A Memoir by Isaac Mizrahi

Audio biographies are always best when the author has the required talent to read his or her own material. Learning about the trials, tribulations, and triumphs of someone else’s life can give perspective to your own. Recently I listened to Isaac Mizrahi read his autobiography, I.M: A Memoir. As a gentile from the heartland, learning about a young Syrian Jew growing up in Brooklyn was a little like binge watching The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, except from a gay male perspective.

Audio biographies are always best when the author has the required talent to read his or her own material. Learning about the trials, tribulations, and triumphs of someone else’s life can give perspective to your own. Recently I listened to Isaac Mizrahi read his autobiography, I.M: A Memoir. As a gentile from the heartland, learning about a young Syrian Jew growing up in Brooklyn was a little like binge watching The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, except from a gay male perspective.

Isaac shares stories of his life with two older sisters and his fashion forward mother, Sarah. Fabric and clothing design were passions as a young boy as was constructing puppets with the sewing machine his father gave him. Isaac provided critiques on his sisters’ ensembles for the high holidays and paid close attention to how his mother shopped, accessorized, and was stylish on a budget. His father, Zeke, manufactured children’s clothing, selling coats and suits to stores like JCPenney and Sears. This was Isaac’s first exposure to the retail industry. Isaac’s relationship with his father was often difficult. At Yeshivah of Flatbush, an Orthodox Jewish school, the faculty told Isaac that God hated homosexuals and his father’s sentiments echoed this intolerance. The early death of Zeke demanded many religious obligations for Isaac to perform none of which he was able to complete with total conviction. This loss gave Isaac the opportunity to come out to his family, but remaining faithful to Judaism in the long term was untenable.

Isaac worked for Perry Ellis, Ralph Lauren, and others, leading him to begin designing his own clothing. He debuted his first signature line in 1987. Many of us remember Joan Rivers asking “who are you wearing?” to be answered with the name Isaac Mizrahi. The nature of life in a clothing design studio can be frenetic and unhinged, racing to meet deadlines and trying to satisfy high profile and often-difficult clients. The 1995 documentary Unzipped is an iconic representation of this period in fashion featuring many of the supermodels and personalities of the ‘90s. It highlights Isaac preparing for his 1994 fall collection after receiving critical reviews from his previous show.

Struggling with his own body image and insomnia were constant difficulties in his multi-faceted career, from hosting talk shows to cabaret singing. Ending his clothing line and transitioning to other projects, the speed of life settled into a more comfortable and healthy pace. Now Isaac is a spokesperson for his brand on QVC and is a judge on Project Runway All Stars. He continues to live in New York City with his husband Arnold and their two rescue dogs. Since his birth, the world has been Isaac’s stage. I only wish the stages were a little closer to the Midwest.

Mizrahi, Isaac. I.M.: A Memoir. New York: Flatiron Books, 2019

Friday Reads: The Size of the Truth, by Andrew Smith

Andrew Smith is best known for writing young adult novels that range from darkly humorous and apocalyptic, like Grasshopper Jungle and Rabbit & Robot, to angst-filled and realistic, like Winger and Stand-off. In a notable departure, Smith just debuted his first middle grade book, the mostly realistic but tiny bit surreal The Size of the Truth. It’s a prequel of sorts, filling in the backstory of Sam Abernathy, Ryan Dean’s precocious, cooking-show-loving roommate from Stand-off.

Andrew Smith is best known for writing young adult novels that range from darkly humorous and apocalyptic, like Grasshopper Jungle and Rabbit & Robot, to angst-filled and realistic, like Winger and Stand-off. In a notable departure, Smith just debuted his first middle grade book, the mostly realistic but tiny bit surreal The Size of the Truth. It’s a prequel of sorts, filling in the backstory of Sam Abernathy, Ryan Dean’s precocious, cooking-show-loving roommate from Stand-off.

Sam narrates The Size of the Truth, jumping back and forth in time between the defining experience of his young life, which occurred when he was four and got trapped at the bottom of a well for three days, and his present, as an eleven-year-old eighth grader dealing with baggage left over from that event. The baggage includes severe claustrophobia and an inability to escape his identity, in Blue Creek, Texas, as “The Little Boy in the Well.” It also infects Sam’s relationship with his parents, who plot out every aspect of his life in an obsessive effort to “[make] sure [he’d] never have the freedom to fall into unseen holes in [his] future” (71). (Their version of his life involves Science Club, AP Physics, Blue Creek Magnet High School, and MIT, as opposed to the culinary school Sam aspires to attend.) Sam, for his part, goes along with this micromanagement because he doesn’t want to “do something as foolish as fall into a hole and disappoint [his] parents ever again” (71).

Sam’s challenge, in the course of this story, is to internalize the truth imparted to him by a probably-not-real talking armadillo named Bartleby (this is the surreal element referenced above), who he remembers visiting him during his time in the well: “don’t go living your life only trying to avoid holes” (172). Sam also needs to learn that other people aren’t always who he’s believed them to be either—most notably, James Jenkins, the older “murderous” boy Sam has always blamed for the well incident. (Everyone in Blue Creek assumes James is destined for football stardom when, unbeknownst to them, he has a whole other identity in Austin, Texas, where his mother lives.)

I don’t know how middle school me would have responded to Smith’s latest book, but it definitely strikes a chord with adult me. In particular, as the mother of a 17-year-old who I want to not only protect but also see flourish and succeed, it’s a good reminder of the damage we do when we project our expectations on to others, filling in their blanks without really listening to their truth.

Smith, Andrew. The Size of the Truth. New York: Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, 2019.

Friday Reads – Palaces for the People by Eric Klinenberg

It is unusual for libraries to be the subject of best-selling books and nationally distributed films. Though, in recent times, that has happened with the publishing of Susan Orlean’s The Library Book, Eric Klinenberg’s Palaces for the People, Emilio Estevez’s film, The Public, and Frederick Wiseman’s epic film documentary, Ex Libris.

It is unusual for libraries to be the subject of best-selling books and nationally distributed films. Though, in recent times, that has happened with the publishing of Susan Orlean’s The Library Book, Eric Klinenberg’s Palaces for the People, Emilio Estevez’s film, The Public, and Frederick Wiseman’s epic film documentary, Ex Libris.

In Palaces for the People, libraries are a subject not the subject. The book title comes from Andrew Carnegie’s philanthropic initiative to support the building of libraries as palaces of the people. Klinenberg contends that public libraries are essential to social infrastructure – defined as the “physical places and organizations that shape the way people interact.” Klinenberg, a sociologist, reflects on how common spaces, like libraries, can aid in repairing our degraded and fractured civic life. He points to a number of “palaces” vital to restoring the common good – parks, diners, farmer’s markets, churches, and more. As for libraries, Klinenberg writes that “Libraries are the kinds of places where ordinary people with different backgrounds, passions, and interests can take part in a living democratic culture.”

Klinenberg rightly recognizes that libraries are community places that have value for all – public programs, space for children and teens, reading spaces, broad-based reading materials, public computers, makerspaces, and much more. Some places are not for everyone, libraries are for everyone. Klinenberg says libraries are “the best case of a physical place that is open and accessible to everyone, regardless of age, ethnicity or race, social class, or even citizenship status. They’re places that are defined by generosity of spirit.”

Libraries are not what they could be. Budget reductions over time have taken their toll. Library funding at national, state, and local levels has declined or remained stagnant. Library staffing, public service hours, and collections have declined. A more positive thought is that libraries, resourceful as they are, have sought ways to increase and improve programming, explore new services, and demonstrate imagination in doing more with less. Klinenberg makes the case for social infrastructure investments. His contention is that financial support – investment – brings people together and builds stronger communities, just as important as public and private investment in the physical infrastructure of roads, bridges, and other components. Imagine what would be possible if times could change to add more funding to library budgets.

Eric Klinenberg is a professor of sociology and director of the Institute for Public Knowledge at New York University. He is the coauthor of the #1 New York Times bestseller Modern Romance and the author of the acclaimed books Going Solo and Heat Wave. He has contributed to The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, and This American Life.

Eric Klinenberg. Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life. Crown), 2018.

Friday Reads: Stoner

This book is a bit of false advertising, as it is nothing like the title suggests. Nevertheless, I did stick with it, after learning that Stoner actually is a reference to William Stoner, the main character in the novel by John Williams (1922-1994). The book was originally published in 1965. Stoner tells the story of William, born and raised on a small farm in Missouri, who eventually goes off to Columbia, MO to college. The original plan is for Stoner to complete a degree in agriculture, and then return to implement his knowledge for the benefit of the family farm. However, while in Columbia, Stoner develops an interest in literature, eventually earning his Ph.D. and subsequently teaching at the University in Columbia. While Stoner tells the semi-interesting story of his lackluster marriage, his relationship with his daughter, and life teaching English (including faculty relationships and conflicts), it is really more about his stoicism.

This book is a bit of false advertising, as it is nothing like the title suggests. Nevertheless, I did stick with it, after learning that Stoner actually is a reference to William Stoner, the main character in the novel by John Williams (1922-1994). The book was originally published in 1965. Stoner tells the story of William, born and raised on a small farm in Missouri, who eventually goes off to Columbia, MO to college. The original plan is for Stoner to complete a degree in agriculture, and then return to implement his knowledge for the benefit of the family farm. However, while in Columbia, Stoner develops an interest in literature, eventually earning his Ph.D. and subsequently teaching at the University in Columbia. While Stoner tells the semi-interesting story of his lackluster marriage, his relationship with his daughter, and life teaching English (including faculty relationships and conflicts), it is really more about his stoicism.

After reading more about stoicism, it sounds great in theory, but after reading Stoner I’m not buying what the stoics are selling. For some filler material, I also read a bit of the well-known stoic and Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius (121 – 180 AD), whose book Meditations is a mix of hell yes (“The more we value things outside our control, the less control we have”) and fortune cookie philosophy (“The best revenge is not to be like your enemy”). I dunno, sometimes it seems as though revenge along the style of Ray Donovan or Donnie Yen seems appropriate. Depends on the circumstances I suppose. OK – back to the stoics. Generally speaking, the stoic endures hardship or pain without feelings or complaint, and this is exactly the life of Stoner, sans a few very brief moments of joy and happiness. However, after reading Stoner I realized something I had not thought of before or maybe did not see. And that is that the stoic life seems to not only suffer through hardships without complaint (dispassionate), but to also be void of any passion. Let’s face it — sometimes I like to be passionate about the fact that I’m dispassionate about certain things. And that I think is where Stoner falls short, at least on a philosophical level. On a literary level, it’s an OK read, but man you really come away thinking that Stoner is a real sad sack.

Williams, John. Stoner. NYRB Classics, 2006.

Friday Reads: Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata

Keiko Furukura realized as a child that she was different from everyone else. Her classmates and teachers were increasingly dismayed by her behavior and her family desperately wanted her to be “cured” and become “normal.” Until Keiko found her job at the Smile Mart convenience store during university, she felt doomed to be the odd one out.

Keiko Furukura realized as a child that she was different from everyone else. Her classmates and teachers were increasingly dismayed by her behavior and her family desperately wanted her to be “cured” and become “normal.” Until Keiko found her job at the Smile Mart convenience store during university, she felt doomed to be the odd one out.

But at Smile Mart, the world makes perfect sense. She can follow the employee behavior manual, mimic the speech and dress of her co-workers, and everyone seems happy with her. Flash-forward 18 years; working part-time at a convenience store is no longer enough to keep her friends and family satisfied, and Keiko finds that it is time for a change.

This story gives some insight into the importance of conformity in Japanese culture; it is more important to Keiko’s friends and family that she meet societal expectations, to get married or find a real career path, than to live a content life as a misfit…even if that marriage is dysfunctional or the career makes her unhappy. Keiko must decide if she will do as others think she should… or be true to herself. A short read, this humorous yet heart-breaking tale may have you wondering who the misfits really are.

Murata, Sayaka. Convenience Store Woman. Translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori, Grove Press, 2018.

Friday Reads: ‘Tales from the Perilous Realm’ by J.R.R. Tolkien

J.R.R. Tolkien is best known as the creator of Middle-earth, the setting of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit. But, did you know that he wrote other stories that don’t take place in Middle-earth?

J.R.R. Tolkien is best known as the creator of Middle-earth, the setting of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit. But, did you know that he wrote other stories that don’t take place in Middle-earth?

In addition to being a fantasy author, Tolkien was an academic. He wrote modern translations of Sir Gawain & The Green Knight and Beowulf as well as the narrative poems The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún, based on Norse mythology, and The Fall of Arthur, inspired by the legend of King Arthur.

Those longer works can be a bit hard to get through. Personally, I prefer his shorter original fairie tale novellas. Some of them are collected in Tales from the Perilous Realm:

Roverandom is the story of a dog who is turned into a toy by an angry wizard and recounts his adventures as he searches for a way to undo the spell.

Farmer Giles of Ham is an accidental hero, who must deal with a dragon who has invaded his village.

Smith of Wootton Major is the tale of a blacksmith who, after eating a magical cake, is able to enter the Land of Faery.

Leaf by Niggle is a short story about a painter struggling to finish his greatest work.

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil is the only selection in this book related to Middle-earth. It is a collection of poems written by Hobbits, such as Bilbo Baggins and Sam Gamgee.

I have discovered that Tolkien is a fun and creative storyteller, in all forms. If you’ve only read his books based in Middle-earth, I highly recommend checking out his other stories.

Friday Reads: The Remarkable Journey of Coyote Sunrise by Dan Gemeinhart

Coyote (12) travels with Rodeo (her father, but don’t call him that) in a refitted old school bus. They go where any whim takes them and only think of the future. One day when Coyote talks to her grandma, she learns the park in their old neighborhood is going to be leveled to become housing. Now Coyote must get home, somewhere Rodeo will not go, so she will trick him into it. She must retrieve the memory box she, her sisters and her mom buried in the park five years ago. They are in Florida and need to get to Washington state in four days, without Rodeo realizing where they are going.

Coyote (12) travels with Rodeo (her father, but don’t call him that) in a refitted old school bus. They go where any whim takes them and only think of the future. One day when Coyote talks to her grandma, she learns the park in their old neighborhood is going to be leveled to become housing. Now Coyote must get home, somewhere Rodeo will not go, so she will trick him into it. She must retrieve the memory box she, her sisters and her mom buried in the park five years ago. They are in Florida and need to get to Washington state in four days, without Rodeo realizing where they are going.

Along the way they give some other travelers a lift and an interesting fellowship develops. First, she finds a kitten who is unusually quiet and seemingly knowing about what humans need, a bit like Coyote herself. She invites Lester to ride with them to Montana to reunite with his former girl. Salvador and his mom help Coyote out of a tough spot right when their car dies, so they join the group. A couple of others join for a spell, including a considerate goat named Gladys. Heartfelt and full of fun too, this book is able to move from silly to touching and bring a tear to your eye. It is aimed at upper elementary to early middle school readers, or for anyone who enjoys a good road trip book about family.

Other books by the author include Good Dog, Scar Island and The Honest Truth.

Gemeinhart, Dan. The Remarkable Journey of Coyote Sunrise. Henry Holt and Co., 2019.

Friday Reads: The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating by Elisabeth Tova Bailey

“I found a snail in the woods. I brought it back and it’s right here beneath the violets …”

“Is it alive?”

This is the first question Bailey asks of the snail in her book, The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating, in which she recounts her survival through a debilitating relapse of her chronic illness. Once a traveler and gardener, she is rendered bedbound and alone, save for the occasional visits of loved ones and her caregiver. And then she is gifted the company of a wild woodland snail, brought from its habitat with a friend’s potted offering of wild violets.

As it so happens, the snail is alive, and its motion and unique liveliness breathes purpose into Bailey’s stalled life.

The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating is a small book. Its pages number at 170; 191 if you count the acknowledgements and bibliography. It’s a quick read that gets technical at times but never becomes wholly inaccessible. Its style, complete with pages dotted here and there with monochrome drawings of snails, is a tribute to the 19th century naturalists of whom Bailey seems fond, and she follows in their footsteps – or, rather, to borrow her imagery, she glides along the slime trail they left behind.

Bailey draws from scientific literature and poetry in rhythm with her observations, making the book one-part informative essay and one-part ode. Peppered in between discussions of the snail’s locomotion, diet, and evolution are the chronicles of her illness, told in an almost tangential fashion, secondary but parallel to the snail’s life, where she both wishes to be more like the snail and longs to feel human again. Is it alive, she asks of the snail and its stillness during their first introduction. Am I alive, she seems to ask; or, the darker question that lingers, one with an answer she couldn’t know, will I survive this?

The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating is best enjoyed in the perfect stillness that might allow oneself to overhear a snail at its dinner. Bailey asks the reader to slow down and ponder – and wonder – at nature and its small, unnoticed creatures and their tiny, significant lives. The reward for your patience is a quiet sort of jubilation and a feeling of hopeful resilience.

Bailey invites us to consider the snail and, in doing so, asks if we might also see ourselves.

Bailey, Elisabeth Tova. The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2010.

Friday Reads: Inheritance by Dani Shapiro

What do our parents really leave us? Is it money, or a house? Seeing my father’s eye’s when I look in the mirror or my mother’s nose? Is it memories, the good and the bad? What if you found your dad wasn’t your biological father? That all the family history, the aunts and uncles, the cousins and grandparents, that they didn’t really belong to you. At least not in the way you thought. This is the basis for Dani Shapiro’s poignant and timely memoir, “Inheritance: A Memoir of Genealogy, Paternity, and Love.” This is not just the tale of the author’s search for her biological father, but her desire to know the secrets her parents kept.

What do our parents really leave us? Is it money, or a house? Seeing my father’s eye’s when I look in the mirror or my mother’s nose? Is it memories, the good and the bad? What if you found your dad wasn’t your biological father? That all the family history, the aunts and uncles, the cousins and grandparents, that they didn’t really belong to you. At least not in the way you thought. This is the basis for Dani Shapiro’s poignant and timely memoir, “Inheritance: A Memoir of Genealogy, Paternity, and Love.” This is not just the tale of the author’s search for her biological father, but her desire to know the secrets her parents kept.

I listened to the audiobook, published by Random House, and narrated by the author herself. Listening to the author tell her own story, hearing her voice and emotion as she recounts the journey she takes after this discovery made the experience even more enjoyable. I choose this book in my attempt to read more non-fiction this year, and it didn’t disappoint.

Shapiro, D. (2019). Inheritance: A Memoir of Genealogy, Paternity, and Love.

Posted in Books & Reading, General

Tagged #FridayReads, Book Review, Dani Shapiro, Friday Reads, Inheritance, Memoir

Leave a comment

Friday Reads: The Library Book by Susan Orlean

The Library Book by Susan Orlean is a necessary and fascinating read for anyone who has used a library—even more so for anyone who works in a library. Orlean tells the story of the Los Angeles Central Library, its founding and its operation, and about a dramatic 1986 fire and the following investigation. Of special interest to Nebraskans, the building itself was designed by Bertram Goodhue, who was also the architect for another building you might be more familiar with: the Nebraska State Capitol building.

The way Orlean tells the story is as interesting as the investigation itself. The book is true crime, history, biography, and homage. She describes her own emotional connection to visiting her hometown library with her mother as a child, and then returning to libraries much later, after having a child of her own, and she begins to appreciate what an incredible societal wonder the modern library is.

Orlean also tells the stories of pioneers, free thinkers, and risk takers who made the Los Angeles Central Library possible, like Mary Foy, who became the head librarian of the Los Angeles Central Library in 1880, when men still dominated the field—and when she was only eighteen years old. With thoughtfulness and sensitivity, she talks about the emotional aftermath of the 1986 fire, for the workers and patrons of the Central Library, with personalized detail. She addresses the realities of the twenty-first century public library with respect and without sentimentality.

I dragged my feet finishing this book, because I didn’t want it to end. I knew from the formatting of the first page—I won’t give away how each chapter is introduced—that I was reading a book about libraries by someone who knew them and loved them.

If you’re old enough to remember 1986, but you don’t remember the Los Angeles Central Library fire, it might be because another catastrophic event happened a few days before in Chernobyl, which overshadowed the fire in the news. After you read the book, you might want to watch news clips and video of the time—and view other reactions to the book. The story told by the book has encouraged a reckoning and remembering by those affected, and it is powerful.

I took my copy of the book on a field trip to another library designed by Goodhue—in the aforementioned Nebraska State Capitol building. Pretty library photos will be on social media soon, and I will add a link here when that happens.

Orlean, S. (2018). The library book.

Friday Reads: All Systems Red (The Murderbot Diaries #1) by Martha Wells

“As a heartless killing machine, I was a terrible failure.”

“As a heartless killing machine, I was a terrible failure.”

Murderbot (as they call themself) is a part organic/part machine SecUnit (security unit) who is contracted out by The Company to various research and exploration teams traveling to other planets to keep them safe, and to keep an eye on what they’re doing. Unlike other SecUnits, however, this particular one has hacked their own (cheaply made) governor module so they no longer have to follow the Company’s strict protocols. Rather than turning against all humans or anything overly violent, Murderbot just wants to be left alone to watch thousands of hours of sci-fi/adventure soap operas and to do the bare minimum of work (just enough so no one realizes they now have free will).

The current job includes a group of humans who are exploring a planet for scientific reasons that don’t matter much to Murderbot. This is a fairly easy job until equipment starts to fail, creatures start attacking, and vital pieces of information seem to be missing which puts the humans all in danger. Now they must find out who is behind the conspiracy and what’s going on, keep the humans safe from other (more heartless) robots, and get them all off of the planet while desperately trying to avoid more social interaction than is necessary.

All Systems Red is the first novella of four in The Murderbot Diaries which all follow our snarky SecUnit. Quick reads with fast-paced stories, engaging characters, lots of snarky humor, cyborg/robot/human battles, and tentative friendships.

- All Systems Red

- Artificial Condition

- Rogue Protocol

- Exit Strategy

Friday Reads: Foundryside: A Novel, by Robert Jackson Bennett

Great world buildings, eccentric characters, and a solid plot that keeps me guessing, will always catch my attention, and Foundryside, by Robert Jackson Bennett has all of that and more. In so many ways it’s also unusual–set in a tropical seaport town, of a world that has seen an apocalypse wrought by an unusual type of magic called “scriving” by the surviving, thriving, inhabitants.

Foundryside by Robert Jackson Bennett

The merchant houses of Tevanne, rediscovered the art, and used the power of “scriving” to conquer other cities, create empire, and spy on each other. The tools they create are powerful, arrows that vibrate so hard as they go through the air that they disintegrate; rapiers that accelerate when put into motion, because they believe they’re going so much faster, and can go through tree trunks; and suites of armor that barely need inhabitants to kill. So of course, they create these items, and more, behind their own walls. Each merchant house is nearly a city-state with their own culture.

The people unlucky enough not to be born to the houses, or useful to them, live in the commons, the areas outside their walls. Like Sancia, a very good thief, who has a rare ability of being able to listen, and understand the scrivings on objects–floors, walls, and locks. A job comes her way through her fence to steal an item that’s just arrived in Tevanne. Which is when everything goes wrong, of course. The item is a very old, rare, scrived artifact, from the original practitioners of scriving, and talks, in a way. Its name is Clef. And he’s freaked out that she can hear him. She’s very freaked out that he can talk! And life just gets more complicated from there, with scions of merchant houses run amok, scrived humans (which shouldn’t exist), the already slightly crazy practitioners of a fractured art, and a lot of people doing impossible things such as shooting crossbow bolts at our heroes.

Included here is an interview with the author on SYFYWire.

Foundryside, Robert Jackson Bennett, Crown, New York, ISBN 978-1-5247-6036-6

Posted in Books & Reading, Uncategorized

Tagged #FridayReads, Dark Fantasy, Fantasy, Foundry, Friday Reads, Robert Jackson Bennett, Young Adult

Leave a comment

Friday Reads: The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho

This boo k has been sitting on my bookshelf, unread, for about a decade. I bought it because a few friends had raved about the life-altering, mind-bending power of this book. Needless to say, I was skeptical.

k has been sitting on my bookshelf, unread, for about a decade. I bought it because a few friends had raved about the life-altering, mind-bending power of this book. Needless to say, I was skeptical.

I didn’t say anything back them, but I suspected the only reason my friends enjoyed the book is because they were already in the middle of changing their own lives when they happen to stumble upon the book. The Alchemist has the ability to pour gas on a lit fire to make the flames explode upward. But it cannot apply spark to the flint over dead leaves.

The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho is the story of a young man named Santiago who wants to see the world. He starts out as a shepherd who quietly enjoys what he does. But the endless horizon calls out to him. Thus his journey begins. Along the way, he meets a variety of mystically inclined individual(s) who provide him with endless philosophical advice to drive him towards his own Personal Legend.

He winds up in pursuit of treasure near the pyramids in Egypt. It’s a wild ride. When I tried to read this book the first time, I was turned off by phrases like ‘Personal Legend’, ‘Soul of the World’, and other over-the-top phrases. Ten years later, when the book called to me again, I realized that these are just phrases. Depending on your own personal beliefs, you can mentally exchange these phrases for words that speak to you. The book was already translated once from the Brazilian author’s native Portuguese.

For me, this book was a way to see myself from a more global perspective. We will all travel through life, meeting different people who will teach us different things. As I learn more about how people in other parts of the world live, I find my own Personal Legend shifting. The small irritations in life don’t seem to matter quite as much. I have food, clean water, access to learning tools, plenty of books, all things necessary to a good life. Why not help those who don’t have access to that already?

If you’re ready to change your life, or are open to seeing other ways of life, this could be a good book. It’s a quick read, and can be a great catalyst for change. As you’re reading your own meaning into the book, keep in mind that sometimes the journey is vastly more important than the end goal.

Maybe I will pick up this book in another ten years and see a completely different story.

Friday Reads: The Bookman’s Tale: A Novel of Obsession, by Charlie Lovett

Mystery fiction has many subgenres: hard-boiled, cozy, police procedural, etc. One particular subgenre of interest to lovers of books is that of the bibliomystery, and in recent years, I’ve found that I love to read, or listen to, books that fall in this bibliomystery category. If you do an online search you will find many authors that write bibliomysteries. My favorites are John Dunning’s Cliff Janeway series, John Grisham’s Camino Island, Bradford Morrow’s Prague Sonata and bibliomysteries by Charlie Lovett, which leads me to today’s Friday Reads post: The Bookman’s Tale: A Novel of Obsession, by Charlie Lovett.

Mystery fiction has many subgenres: hard-boiled, cozy, police procedural, etc. One particular subgenre of interest to lovers of books is that of the bibliomystery, and in recent years, I’ve found that I love to read, or listen to, books that fall in this bibliomystery category. If you do an online search you will find many authors that write bibliomysteries. My favorites are John Dunning’s Cliff Janeway series, John Grisham’s Camino Island, Bradford Morrow’s Prague Sonata and bibliomysteries by Charlie Lovett, which leads me to today’s Friday Reads post: The Bookman’s Tale: A Novel of Obsession, by Charlie Lovett.

Hay-on-Wye, every bibliophile’s dream destination in England, 1995. Peter Byerly isn’t sure what drew him into this particular bookshop. Nine months after the death of his beloved wife Amanda left him shattered, Peter, a young antiquarian bookseller, relocates from North Carolina to the English countryside, hoping to outrun his grief and rediscover the joy he once took in collecting and restoring rare books. But upon opening an eighteenth-century study of Shakespeare forgeries, he discovers a Victorian watercolor of a woman who bears an uncanny resemblance to Amanda. Peter becomes obsessed with learning the picture’s origins and braves a host of dangers to follow a trail of clues back across the centuries—all the way to Shakespeare’s time and a priceless literary artifact that could prove, once and for all, the truth about the Bard’s real identity, and definitively prove Shakespeare was, indeed, the author of all his plays.

Friday Reads: The Keeper of Lost Causes: The First Department Q Novel by Jussi Adler-Olsen

This book came to me by way of a recommendation from a book club member who also reads mysteries and series. I have read Nordic Noir authors Jo Nesbo, Steig Larsson, and Henning Mankell, but I had not read any books from the Department Q Series by the Danish author Jussi Adler-Olsen. All of the authors have a reputation for their dark descriptions of crime, twisted plots, and grizzled detectives. This book follows a popular recipe for sleuths: troubled personal relationships, inability to get along with co-workers, abuser of substances, and a brilliant deductive mind. The plot goes back and forth between the last week Detective Carl Mørck was a homicide detective and the present, when he is assigned to lead a newly created Department Q – a literal closet in the basement of the police department where the most difficult cold cases reside.

This book came to me by way of a recommendation from a book club member who also reads mysteries and series. I have read Nordic Noir authors Jo Nesbo, Steig Larsson, and Henning Mankell, but I had not read any books from the Department Q Series by the Danish author Jussi Adler-Olsen. All of the authors have a reputation for their dark descriptions of crime, twisted plots, and grizzled detectives. This book follows a popular recipe for sleuths: troubled personal relationships, inability to get along with co-workers, abuser of substances, and a brilliant deductive mind. The plot goes back and forth between the last week Detective Carl Mørck was a homicide detective and the present, when he is assigned to lead a newly created Department Q – a literal closet in the basement of the police department where the most difficult cold cases reside.

Thinking this is a promotion, Carl soon realizes this position will take him out of action. The first case he selects from boxes and boxes of cold cases involves trying to find a missing politician captured five years ago and assumed by many to be dead. Carl is assigned a staff of one – a man with a mysterious past named Hafez el-Assad. Initially Carl views Assad as not much more than a driver and personal assistant, but Assad makes himself a real partner in solving cases and becomes invaluable to the department. At home, Carl is separated from his wife Vigga, is a sometimes guardian to his stepson, and is in need of the rent that is paid by his opera-loving lodger to make ends meet. This book will take you on a ride that is sinister and horrifying. Expect that with Nordic Noir.

For those who have Amazon Prime, the first three books in the Department Q series are also films in Danish with subtitles. I found the casting to be spot on and the Danish countryside both beautiful and foreboding.

Adler-Olsen, Jussi, The Keeper of Lost Causes: The First Department Q Novel. New York: Dutton, 2011.

Friday Reads: Daring to Drive: A Saudi Woman’s Awakening, by Manal al-Sharif

Daring to Drive is the memoir of Manal al-Sharif, a Saudi Arabian women’s rights activist who spent time in prison after participating in the 2011 Saudi women’s driving campaign. While the first two and final four chapters focus on her driving activism, the middle eight are a chronological account of her life, beginning on April 25, 1979, the day of her birth. In my view, the real drama of the narrative is in seeing how al-Sharif transforms from a young girl, strictly controlled by Saudi custom and a fundamentalist version of Islam, to a woman who challenges the status quo at great personal cost.

Daring to Drive is the memoir of Manal al-Sharif, a Saudi Arabian women’s rights activist who spent time in prison after participating in the 2011 Saudi women’s driving campaign. While the first two and final four chapters focus on her driving activism, the middle eight are a chronological account of her life, beginning on April 25, 1979, the day of her birth. In my view, the real drama of the narrative is in seeing how al-Sharif transforms from a young girl, strictly controlled by Saudi custom and a fundamentalist version of Islam, to a woman who challenges the status quo at great personal cost.

One value in reading an account like al-Sharif’s is the window it provides into the restrictive, brutal nature of Saudi life, especially for women. In Saudi Arabia women are completely dependent on male guardians (usually fathers or husbands) or on mahrams (male relatives whom they cannot marry, such as brothers, uncles, or even sons) to accompany them on any official business. To illustrate her point that in Saudi eyes “death is preferable to violating the strict code of guardianship and mahrams” (7), al-Sharif cites several cases where women died when male paramedics weren’t allowed to treat them because their guardians or mahrams weren’t present. And of course, women couldn’t drive, even if, like al-Sharif, they owned cars and had foreign driver’s licenses. (Note: Authorities finally lifted the ban on women driving on June 24, 2018.) Instead, women relied on, and frequently suffered harassment by, male taxi drivers or “an informal network of men with cars who illegally transport female passengers” (9).

For the most part, the cultural landscape al-Sharif describes appears quite alien. Occasionally, though, one feels an uncomfortable flicker of familiarity. For example, on the topic of harassment al-Sharif writes “the authorities . . . always blame the woman. They say she was harassed because of how she looked or because of the way she was walking or because she was wearing perfume. They make you the criminal” (11). al-Sharif’s decision to wear a hijab, which left her face uncovered, instead of a niqab, in public was seen by men as an invitation to shout slurs, like “whore” and “prostitute,” at her. The degree of coverage hardly seemed to matter though, as even a woman who left only her eyes exposed was reportedly told by religious police to cover them because they were “too seductive” (234).

So what allowed al-Sharif to reject the shackles of her culture? To achieve a broader perspective on Saudi customs and fundamentalist beliefs? After reading her memoir, I’d say that, in addition to innate curiosity, it was education, internet access, and exposure to people from other parts of the world – exactly the things repressive regimes and conservative religions invested in maintaining the status quo typically fear.

al-Sharif grew up with a mother who prioritized education for both her daughters and her son. And even though the schools al-Sharif attended growing up initially fanned the flames of her extremist religious beliefs, her academic achievements ultimately got her accepted to King Abdulaziz University in Jeddah. There, she received a small monthly allowance from the school, which gave her a first taste of financial independence. She also had her radical religious beliefs tested for the first time by fellow students who didn’t follow all the same practices she did. Perhaps most importantly, she signed up for internet access in order to complete and submit her homework. Though her original intent had been to avoid reading anything that might undermine her beliefs, she ultimately couldn’t resist exploring political analysis, world news, and diverse opinions. “Nothing,” she wrote, “did more to change my ideas and convictions than the advent of the Internet and, later, social media” (132-133).

Finally, after graduating, her university degree got her a good job at Aramco, the Saudi state oil company, where she worked with not only Saudi men, but also foreigners. In 2009, as part a professional exchange program, she got to live and work in the United States for a year. During this time abroad, she learned to drive, got a New Hampshire driver’s license, and rented a car at company expense. She went skiing and skydiving, got a public library card, attended a play in which two men kissed, learned about Rosa Parks and the civil rights movement, took up photography, and befriended a Jewish woman, none of which she could or would have done in Saudi Arabia. Her year in the United States was definitely a turning point for her; though she went back to Saudi Arabia at the end of it, she returned a completely different person. As she writes, “ the true culture shock occurred not when I landed in America, but much later, after I had returned home” (203). This is when her activism began in earnest.

al-Sharif, Manal. Daring to Drive: A Saudi Woman’s Awakening. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017. Print.

Friday Reads: The Reckoning, by John Grisham

I have read many of John Grisham’s legal thrillers dating back to his second book, The Firm (1991). I didn’t read his first, A Time to Kill. I only saw the movie. It is admirable that a writer can publish a new bestseller each year, and sometimes more than one. Grisham’s novels now number 41. In addition, he has published short stories, nonfiction, and young adult books. Grisham is a creative and clever writer. His most recent book, The Reckoning, is, to me, among his best.

I have read many of John Grisham’s legal thrillers dating back to his second book, The Firm (1991). I didn’t read his first, A Time to Kill. I only saw the movie. It is admirable that a writer can publish a new bestseller each year, and sometimes more than one. Grisham’s novels now number 41. In addition, he has published short stories, nonfiction, and young adult books. Grisham is a creative and clever writer. His most recent book, The Reckoning, is, to me, among his best.

The book is set in 1946 in Grisham’s familiar rural Ford County, Mississippi. Grisham’s experiences there, including an early career as a criminal defense attorney and state legislator, offer informed and useful background for his writing. Pete Banning is the book’s central character – a kind and respected cotton farmer from a prominent family with deep roots in the community. Banning is a West Point graduate, a World War II infantry officer, prisoner of war escapee, and war hero decorated for his leadership and accomplishments as a guerrilla fighter in the Philippines. Thought of as killed in action, Banning’s surprise return home after the war was followed by a shocking criminal act that disrupts his family and the entire community. Banning refuses to offer an explanation for his actions. Why would someone so admired, responsible and respected do what he did? The mystery carries through the book to an unexpected and surprising conclusion.

Of the book’s more interesting chapters are those involving Banning’s wartime service with the Army in the Philippines. There is rich, well-researched, detail of the U.S. Army’s actions, the Bataan Death March, prisoner of war experiences, and guerilla warfare. Equally interesting is how Grisham creates his storylines. For The Reckoning, Grisham contends that the story came from those told among state lawmakers, gathered together for evening conversations. Grisham appears not sure whether the Banning story was based on a real or imagined incident. Either way, the story is compelling and will keep the reader turning pages to the surprising ending.

Grisham, John. The Reckoning. New York: Penguin Random House, 2018.

Friday Reads: The Wrecking Crew: The Inside Story of Rock and Roll’s Best-Kept Secret

A little while ago, I had just finished reading The Wrecking Crew: The Inside Story of Rock and Roll’s Best-Kept Secret and I was listening to a story on NPR about music students attending the Berklee College of Music in Boston. Ironically, the story highlighted current student musicians that were contributing to the music world in a way quite similar to the wrecking crew of the 1960’s and 1970’s. You see, the original wrecking crew was a collection of backup (or maybe background would be a more appropriate word) musicians that played on numerous studio recordings. Like the Berklee music students, the wrecking crew played on jingles, theme songs, film scores, and commercials (the Berklee students have expanded to playing music for podcasts, video games, and other things).

A little while ago, I had just finished reading The Wrecking Crew: The Inside Story of Rock and Roll’s Best-Kept Secret and I was listening to a story on NPR about music students attending the Berklee College of Music in Boston. Ironically, the story highlighted current student musicians that were contributing to the music world in a way quite similar to the wrecking crew of the 1960’s and 1970’s. You see, the original wrecking crew was a collection of backup (or maybe background would be a more appropriate word) musicians that played on numerous studio recordings. Like the Berklee music students, the wrecking crew played on jingles, theme songs, film scores, and commercials (the Berklee students have expanded to playing music for podcasts, video games, and other things).

So The Wrecking Crew documents the lives of these studio musicians, how they started and expanded in the business, and their interactions with some of the writers, producers, arrangers, and other notable artists. These include, among others, Brian Wilson, Sonny and Cher, Simon and Garfunkel, John Lennon, Frank Sinatra, and the Mamas and the Papas. While one of the more well-known members of the crew was Glen Campbell (who also toured as one of the Beach Boys), the book also focuses on drummer Hal Blaine and guitarist Carol Kaye (shown here hilariously giving Gene Simmons a lesson on bass). Incidentally, the name wrecking crew, penned by Hal Blaine, is disputed by Carol Kaye, who mentions that the group of musicians weren’t generally known as such (but sometimes called “the Clique”). Call them whatever you choose, but this set of musicians were the go-to’s when it came to studio recording, and the point is that the work was good enough for them to earn a living doing it. Most of the recorded music you hear from this time has these musicians playing on it instead of the actual bands that toured. And the kicker is that you would never know it; most of the time (if not all of the time) they weren’t credited.

The book also offers an interesting insight into many of the colorful (both in a healthy creative way and sometimes controlling and abrasive) characters in the music world at the time. For the creative but meticulous, think Brian Wilson. For the controlling and abrasive (and sometimes downright crazy), think Phil Spector. The Wrecking Crew offers access into not only these major artists but also those behind the scenes. A documentary film about the Crew, based on the book, may also be of interest (some of the original footage illustrates things in a worthwhile way).

Hartman, Kent (2013). The Wrecking Crew: The Inside Story of Rock and Roll’s Best-Kept Secret. St. Martin’s Griffin.

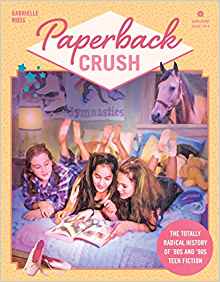

Friday Reads: Paperback Crush: The Totally Radical History of ’80s and ’90s Teen Fiction by Gabrielle Moss

My most vivid memory of second grade was trying to read a Sweet Valley Twins book under my desk during class, only to get caught and kept in from recess. This may have happened multiple times (sorry, Mrs. Wade). From the ages 8 to 12, I heavily favored the sort of books that Gabrielle Moss revisits in her new history of tween and teen fiction from the 1980s and ’90s, Paperback Crush.

My most vivid memory of second grade was trying to read a Sweet Valley Twins book under my desk during class, only to get caught and kept in from recess. This may have happened multiple times (sorry, Mrs. Wade). From the ages 8 to 12, I heavily favored the sort of books that Gabrielle Moss revisits in her new history of tween and teen fiction from the 1980s and ’90s, Paperback Crush.

Flipping through this book was a fun trip down memory lane, with stops along the way in Stoneybrook, CT, Sweet Valley, CA, and Shadyside, OH. Was it classic literature? Not in the slightest. But I would stalk the shelves of my local library or mall bookstore, just waiting for the latest installment of my series-du-jour.

I was surprised at how many titles/series I had forgotten about over the years. Sleepover Friends and Girl Talk, The Face on the Milk Carton, 2 Young 2 Go 4 Boys; their plots had obviously wormed their way into my subconscious, judging by how many clubs I convinced friends to form and how fascinating the idea of having a twin was to tween-age me.

Moss has broken down the 80s/90s teen fiction genre into 7 broad themes (love, friends, family, school, jobs, danger, and terror) and covers the most popular books for each theme, and the knockoffs they inspired. Teen fiction during this time period certainly had its flaws: lack of diversity, corny plot-lines and cheesy cover art, neatly wrapped up endings, but it also fueled the girl-power movement and sparked a lifelong love of reading for many of us. These girls could do anything – take on the school bully, run for class president, deal with an annoying brother or divorcing parents, fight vampires… Interspersed throughout are interviews with authors such as Rhys Bowen, Caroline Cooney, and Christoper Pike, as well as a timeline of teen lit from the turn of the 20th century until more modern times.

If you ever started your own babysitter’s club, or asked yourself if you were an Elizabeth or a Jessica, I would recommend spending a couple of nostalgia-filled hours with this “totally radical” history book.

Moss, Gabrielle. Paperback Crush. Philadelphia, PA : Quirk Books. 2018.

Friday Reads: (Another) Year in Review

As we begin the countdown to 2019, the Nebraska Library Commission is looking back at all the great books we’ve reviewed in 2018!

In our weekly blog series Friday Reads, a staff member at the Nebraska Library Commission posts a review of a book every Friday. Spanning all genres, from short stories to celebrity memoirs, young adult to crime fiction, we’ve shared what we’ve read and why we’ve read it.

Former NLC staffer Laura Johnson created this series to model the idea of talking about books and to help readers get to know our staff a little better. Readers advisory and book-talking are valuable skills for librarians to develop, but they are ones that take practice. We hope that our book reviews will start a conversation about books among our readers and encourage others to share their own reviews and recommendations.

The series has been going strong for 4 1/2 years and has produced over 200 reviews, which are archived on the NCompass blog, or you can browse a list of reviews here.