At the risk of appearing like military-themed books are the only books that Nebraska Library Commission staff read during the summer, I’ve chosen a book that epitomizes this 100th anniversary of the start of World War I—for me. We always talk about books that change our lives and we know that different books can have a huge impact on our lives, sometimes depending on our life-stage and the environment. This is a book that stopped me in my tracks, and continues to this day to influence my ethical perspective and world view.

At the risk of appearing like military-themed books are the only books that Nebraska Library Commission staff read during the summer, I’ve chosen a book that epitomizes this 100th anniversary of the start of World War I—for me. We always talk about books that change our lives and we know that different books can have a huge impact on our lives, sometimes depending on our life-stage and the environment. This is a book that stopped me in my tracks, and continues to this day to influence my ethical perspective and world view.

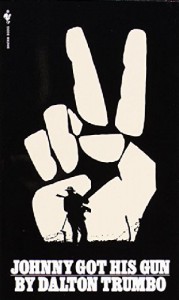

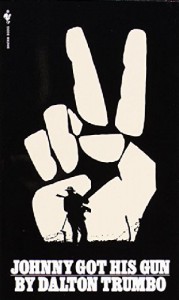

Written in 1938 by Dalton Trumbo, I came across Johnny Got His Gun as a student in a UNL English Literature class in the winter of 1970. It was among dozens of books we were assigned to read, but it is the only one I remember. This book sparked some of the liveliest discussions of my educational career, outside of discussing our original poetry in Ted Kooser’s Poetry Writing class—nothing gets the conversation heated up more than criticizing a classmate’s heartfelt, original works of poetry.

The book begins as a stream-of-consciousness, first-person narration by a severely wounded American soldier, Joe Bonham. Joe slowly comes to realize the extent of his injuries, as the reader gets to know Joe through his richly detailed memories of life before and during the war. The reader shares Joe’s growing horror as he begins to comprehend the loss of his senses one-by-one, interspersed with memories of how those senses gave him a rich full life and made him the man he was: touching, hearing, tasting, seeing, smelling (“There was a smell about the fair grounds you never forgot. A smell you never ceased dreaming of. He would always smell it somewhere back in his mind as long as he lived.”). Joe’s mind is still sharp as he struggles with existential issues: Is he awake or asleep? Is he dreaming or day-dreaming? Can he think his way out of this mess his life has become? What is the “future” for him?

The reader comes to realize the brutal horrors of war as they impact a very real person. Besides being a skillfully crafted story, the characters are so engaging and the depiction of time and place so perfect that reading this book really is like watching a movie. And no matter how badly I wanted to turn my eyes away, it was impossible to stop reading because Joe’s personality and predicament just got under my skin.

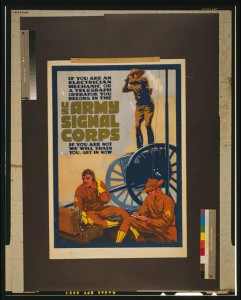

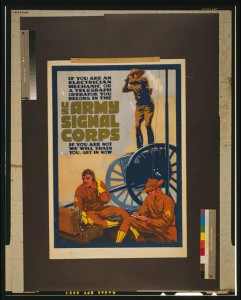

“And we won’t be back ‘till it’s over, over there,” went the words to a popular song used to recruit so many young people. But the reality is—it’s never over, over there—or over here. If the past one hundred years haven’t proved that, I don’t know what will. This war was romanticized beyond belief. The propaganda posters that drew so many to their death illustrate that target marketing was used to convince young people that their way of life depended on their participation in this “war to end all wars.” It’s a real education to take a look at examples of WW I posters at www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/wwipos/ and then contrast them to those of the Vietnam War era at http://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2011/08/protest-posters-from-the-vietnam-era/243029/#slide2.

For many of us in that English class in 1970, the comparison of the Vietnam War to WWI seemed inevitable. As we discussed this book we railed against the war that was killing our friends and former classmates—sitting in our comfortable seats in Andrews Hall, smoking cigarettes, and arguing about making the world safe for democracy. Even though the reality is that these two wars were very different—WWI was the war that introduced us to modern, efficient killing machines and chemicals—there were enough similarities to feed the dissidence that was already growing. Even the author Dalton Trumbo agrees that not all wars should be lumped together when he says, “World War II was not a romantic war… Johnny was exactly the sort of book that shouldn’t be reprinted until the war (WW II) was at an end…Johnny held a different meaning for three different wars. Its present meaning is what each reader conceives it to be, and each reader is gloriously different from every other reader, and each is also changing.”

In May 1970, the semester ended prematurely for many of us that took part in the nationwide student strike. We left the classrooms for informal seminars and teach-ins on the floor in the student union. My grade for that English class was “Incomplete,” but I learned more in that class than I did in most other ones—and this book was a big part of my education.

“Woodstock,” by Joni Mitchell

… And I dreamed I saw the bombers

Riding shotgun in the sky

And they were turning into butterflies

Above our nation

Join us for next week’s NCompass Live: “Tech Talk with Michael Sauers: RFID, Checkout Kiosks, Security Gates, and … a New Way to Check Out”, on Wednesday, August 27, 10:00-11:00 am Central Time.

Join us for next week’s NCompass Live: “Tech Talk with Michael Sauers: RFID, Checkout Kiosks, Security Gates, and … a New Way to Check Out”, on Wednesday, August 27, 10:00-11:00 am Central Time. avid Lee King is the Digital Services Director at Topeka & Shawnee County Public Library, where he plans, implements, and experiments with emerging technology trends. He speaks internationally about emerging trends, website management, digital experience, and social media, and has been published in many library-related journals. David was named a Library Journal Mover and Shaker for 2008. His newest book is Face2Face: Using Facebook, Twitter, and Other Social Media Tools to Create Great Customer Connections. David blogs at

avid Lee King is the Digital Services Director at Topeka & Shawnee County Public Library, where he plans, implements, and experiments with emerging technology trends. He speaks internationally about emerging trends, website management, digital experience, and social media, and has been published in many library-related journals. David was named a Library Journal Mover and Shaker for 2008. His newest book is Face2Face: Using Facebook, Twitter, and Other Social Media Tools to Create Great Customer Connections. David blogs at  It’s been almost a year and a half since the national libraries (and many others) implemented Resource Description and Access (RDA) as their cataloging code. Attend this class to learn about updates that have been made to RDA since implementation and discuss the realities of cataloging (both original and copy) with RDA. The workshop will include time for hands-on creation of RDA records for a variety of items, exploration of the RDA Toolkit, and discussion about where RDA fits in the future of cataloging.

It’s been almost a year and a half since the national libraries (and many others) implemented Resource Description and Access (RDA) as their cataloging code. Attend this class to learn about updates that have been made to RDA since implementation and discuss the realities of cataloging (both original and copy) with RDA. The workshop will include time for hands-on creation of RDA records for a variety of items, exploration of the RDA Toolkit, and discussion about where RDA fits in the future of cataloging.

Best Novel

Best Novel

Best Short Story

Best Short Story

Best Editor, Short Form

Best Editor, Short Form