Search the Blog

Categories

- Books & Reading

- Broadband Buzz

- Census

- Education & Training

- Friday Reads

- General

- Grants

- Information Resources

- Library Management

- Nebraska Center for the Book

- Nebraska Libraries on the Web

- Nebraska Memories

- Now hiring @ your library

- Preservation

- Pretty Sweet Tech

- Programming

- Public Library Boards of Trustees

- Public Relations

- Talking Book & Braille Service (TBBS)

- Technology

- Uncategorized

- What's Up Doc / Govdocs

- Youth Services

Archives

Subscribe

Author Archives: Craig Lefteroff

Friday Reads: Paperbacks from Hell: The Twisted History of ’70s and ’80s Horror Fiction by Grady Hendrix

There are two kinds of people in the world: people who would never read a book called Satan’s Pets and my kind of people. For the latter, Paperbacks from Hell is a delight, a treasure trove of unseemly old horror novels from the days when skeletons were popular cover models and literally any animal could be cast as a monster.

Satan’s Pets and my kind of people. For the latter, Paperbacks from Hell is a delight, a treasure trove of unseemly old horror novels from the days when skeletons were popular cover models and literally any animal could be cast as a monster.

Grady Hendrix is building quite a name for himself as a genre fiction standout. He wrote Horrorstör, history’s greatest novel about a haunted furniture store. And then he wrote My Best Friend’s Exorcism, which he describes as “Beaches meets The Exorcist, only it’s set in the Eighties.” So we’re all pretty lucky that he found the time to compile this book and document the explosion of paperbacks that followed Ira Levin and William Peter Blatty’s surprise success.

It’s a long trek from Rosemary’s Baby & The Exorcist to Viking mummies & psychotic cows, and Hendrix navigates masterfully. If the only noteworthy thing about a book is a shark/grizzly bear fight, that’s all that’s mentioned. More worthwhile works get lengthier treatments and Hendrix maintains his sense of humor throughout. I suspect that it’s probably more enjoyable to read his witty synopses than most of the novels they describe. For example:

“[T]hough we all feel sympathy for the yeti who hates snow in Snowman, how many ski instructors will we allow him to decapitate before we hire a bunch of hunters and Vietnam vets to go after him with crossbows armed with tiny nuclear arrowheads?”

Yes! The proceedings are organized topically, so we spend time with killer clowns, critters, toys, Santas, and skeletons, the last being my favorites due to their assorted jobs. Even in this tiny niche of publishing history, there’s a lot of diversity and the only thing that really unifies these books is that they are all better than Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist.

I’d recommend reading this in print, as it’s the best way to experience the garish covers that are reprinted here, and I’d also advise keeping a notebook handy—this book almost doubled my “to-read” list. A wildly fun read that’s perfect for pumpkin season.

Hendrix, G., & Errickson, W. (2017). Paperbacks from Hell: the twisted history of 70s and 80s horror fiction. Philadelphia: Quirk Books.

Friday Reads: The Comedians: Drunks, Thieves, Scoundrels and the History of American Comedy by Kliph Nesteroff

I’ve had bad book luck lately. Even titles that have won fancy awards have left me feeling pretty unsatisfied. But The Comedians broke my streak—this is a fantastic book, strong enough to be considered the definitive work on the subject. Nesteroff starts off with comedy’s beginnings in Vaudeville and progresses through the radio era, comedy clubs and cable specials, & sketch comedy and variety shows. The title is not a rib—this is a serious, expansive history of comedy as an art form and business—and the treatment of the material might disappoint people who just want a laugh-a-minute romp. But they’ll be missing out if they skip this book.

awards have left me feeling pretty unsatisfied. But The Comedians broke my streak—this is a fantastic book, strong enough to be considered the definitive work on the subject. Nesteroff starts off with comedy’s beginnings in Vaudeville and progresses through the radio era, comedy clubs and cable specials, & sketch comedy and variety shows. The title is not a rib—this is a serious, expansive history of comedy as an art form and business—and the treatment of the material might disappoint people who just want a laugh-a-minute romp. But they’ll be missing out if they skip this book.

The title is also not kidding about the “drunks, thieves, scoundrels” part. Early American comedy had strong links to seedy elements and there are numerous examples of that here—insult comics getting threatened by the Mafiosi sitting in the audience, people dying when cheap comedy clubs collapsed. Beyond its chronicles of actual violence, The Comedians also devotes a fair bit of time to the “crying clown” idea and prevalence of addiction in comedy. Some famous names come across as very broken people and a few emerge as basically forever-unhappy monsters. Some of your favorites might seem a little tarnished after you read it and The Comedians occasionally gets gossipy in a Hollywood Babylon kind of way. But, most of the time, it takes the high road and tells the story of the art form in a fun and engaging fashion. It does for comedy what David J. Skal’s epic The Monster Show did for the history of horror.

One of the most important things about the book is its championing of obscure comedians. Everybody knows the Marx Brothers and Joan Rivers, but it was great to learn about people like Eddie Cantor and Fred Allen, especially at a time when radio-era comedy is instantly accessible through sources like the Internet Archive. If a comedian is/was important, they’re almost certainly here. As I neared the end of the book, I was getting nervous that Andy Kaufman hadn’t been mentioned yet, but The Comedians came through for me. Because of the book’s massive scope, nobody gets tons of spotlight time, but you’ll finish this with a solid understanding of pretty much everything you’d ever want to know about American comedy.

Nesteroff, K. (2015). The Comedians Drunks, Thieves, Scoundrels, and the History of American Comedy. Pgw.

Friday Reads: Hillbilly Elegy by J.D. Vance

Far away from bike paths that lead to grocery stores that sell kale is Appalachia. It runs through West Virginia and eastern Kentucky, and some parts of Tennessee and the Carolinas, too. It’s mostly dirt-poor and the things for which it’s known—family feuds, coal mining, moonshine—seem to have little connection with modern life in other parts of America. These days, unless Appalachia is being mocked, it’s generally ignored.

Which is why it’s strange that this memoir has struck such a chord. It has been sitting atop the bestseller lists for months and has received coverage in tons of major media outlets. On its face, the story doesn’t seem to be widely relatable. J.D. Vance’s family originated in the hills and hollers of rural eastern Kentucky. He experienced the traumas that often shadow poor communities: drug abuse, outbursts of violence, and other self-defeating behaviors. But, unlike many, Vance escaped and prospered, eventually attending Yale and joining a San Francisco investment firm. Hillbilly Elegy reads like a gateway into the world of “Bloody Breathitt” County, Kentucky. But it also details the process through which Vance found a better life outside the region. The book is interesting as a depiction of an overlooked place, but it also works as a coming-of-age story.

And it’s getting talked up as a kind of Rosetta Stone that explains election results. The Times calls it “a civilized reference guide for an uncivilized election”. I’m not sure that I totally buy that. Appalachia is a pretty unique place. I don’t know how much you can port over its attributes to cities in the Rust Belt and so on. It’s worthwhile to examine a culture and community for its own sake, but if you’re just looking for national power brokers or explanations for electoral trends, Hazard, Kentucky might not be where you want to start.

Even if Hillbilly Elegy can’t provide pat answers to complex political questions, it’s still a good book that’s very affecting and ultimately inspiring. If you would like to learn more about the region, I’d recommend this book, as well as two documentaries. American Hollow focuses on the same area and lifestyle described in Hillbilly Elegy and Oxyana viciously captures the prevalence of drug addiction in Appalachian communities. It’s great that attention is being drawn to a part of our country that’s often been forgotten—hopefully, it will lead to some real change for the region.

Vance, J. D. (2016). Hillbilly elegy: a memoir of a family and culture in crisis. New York: Harper.

Friday Reads: Lives of the Monster Dogs by Kirsten Bakis

A Prussian mad scientist relocates to rural Canada, where he uses his mad science skills to create “monster dogs”. The dogs’ intelligence is boosted. Instead of paws, they have prosthetic hands on their forelegs, and implanted voice boxes allow the dogs to speak. They can also walk upright, although some need to use canes for support. Despite these enhancements, the dogs are treated as virtual slaves in their isolated town—so isolated that it retains the scientist’s 19th-century Prussian culture—until the beasts finally revolt. In 2008, the monster dogs arrive in Manhattan, wearing top hats and white ties. Their new city welcomes them and things finally seem to be looking up for the dogs, but a new threat could endanger their entire existence.

A Prussian mad scientist relocates to rural Canada, where he uses his mad science skills to create “monster dogs”. The dogs’ intelligence is boosted. Instead of paws, they have prosthetic hands on their forelegs, and implanted voice boxes allow the dogs to speak. They can also walk upright, although some need to use canes for support. Despite these enhancements, the dogs are treated as virtual slaves in their isolated town—so isolated that it retains the scientist’s 19th-century Prussian culture—until the beasts finally revolt. In 2008, the monster dogs arrive in Manhattan, wearing top hats and white ties. Their new city welcomes them and things finally seem to be looking up for the dogs, but a new threat could endanger their entire existence.

If this synopsis sounds appealing, you should probably read this book. The imaginative premise is definitely the best thing about it. The blend of walking, talking dogs and their old-fashioned Germanic manners is very compelling, and at times this novel has an almost steampunk-like feel. The author skillfully merges the fantastic and the antique, especially in elements like the dogs’ opera libretto, which tells the story of their Canadian uprising.

But there are a few slip-ups. Some of the narration is handled by Cleo Pira, a young writer whom the dogs befriend. Cleo is not an especially interesting character and her adoption by these fascinating dogs seems kind of Twilighty. Sometimes she talks a lot about clothes instead of the talking, walking dogs that wear them. Additionally, some of the plotting is overly loose and the ending seems a bit abrupt and unsatisfying.

But, for me, the monster dogs made up for it. It’s a very audacious idea for a story and, even if everything doesn’t gel perfectly, this is certainly a memorable read. This book was published almost twenty years ago and it is, to date, the author’s only novel. It seems to have gone unnoticed, so here’s hoping that it eventually finds an audience that can appreciate its charms.

Bakis, K. (1997). Lives of the monster dogs: A novel. New York: Warner Books.

Friday Reads: The Celestial Railroad

Like Leonard Nimoy and Thin Lizzy, Nathaniel Hawthorne is somewhat unfairly judged on the basis of his one big hit. I’d wager that lots of you were forced to read The Scarlet Letter at some point in your school days and, like me, did not find it magnificent. Letter is a great book to teach, as it makes literary mechanics very noticeable. But it’s not particularly fun to read, especially when you’re a teen. The prose is dense, words piled high as Hawthorne describes hats and tunics in obsessive detail, and there’s plenty of moralizing. The book’s merits are buried behind the walls of text.

Thankfully, Hawthorne covered a lot of the same themes in his short stories. The excesses that sometimes hampered his novels are excised and what’s left is relatively trim and reader-friendly. There are many echoes of Letter here. Sin and conscience are examined in “Roger Malvin’s Burial”. “The Maypole of Merry Mount” analyzes Puritan society and its distaste for good times. There’s a much better symbol than an A in “The Minister’s Black Veil”. And, though the stories fluctuate in quality, the writing throughout is less laborious than anything in his novels. Hawthorne was a guy writing stories in the 1800s and the stories were mostly about the 1600s and 1700s, so it’s unfair to expect him to read like Janet Evanovich. But the prose here has some life and sometimes he even dips into very black humor:

Thankfully, Hawthorne covered a lot of the same themes in his short stories. The excesses that sometimes hampered his novels are excised and what’s left is relatively trim and reader-friendly. There are many echoes of Letter here. Sin and conscience are examined in “Roger Malvin’s Burial”. “The Maypole of Merry Mount” analyzes Puritan society and its distaste for good times. There’s a much better symbol than an A in “The Minister’s Black Veil”. And, though the stories fluctuate in quality, the writing throughout is less laborious than anything in his novels. Hawthorne was a guy writing stories in the 1800s and the stories were mostly about the 1600s and 1700s, so it’s unfair to expect him to read like Janet Evanovich. But the prose here has some life and sometimes he even dips into very black humor:

“[T]here sat the light-heeled reprobate in the stocks; or if he danced, it was round the whipping post, which might be termed the Puritan Maypole.”

Yikes! My favorite aspect of these stories is the treatment of the Puritans. Hawthorne was viewing America’s past from the rapidly-changing nineteenth century. Transcendentalists like Emerson and Thoreau were popularizing sensitive, romantic spirituality—pretty much the polar opposite of hard, cold Puritanism. And yet Hawthorne never really depicts Puritans as simply primitives or America’s embarrassing, witch-hating grandparents. He portrays the past in an even-handed way, not as a bunch of villains and their victims: the “immitigable zealots” of “Merry Mount” are also the anti-despots of “The Gray Champion”. Both good and bad get their time in the spotlight. Scarlet Letter and House of Seven Gables covered much of the same ground, but it’s conveyed more effectively in these short stories.

If you have sad memories of Hawthorne, I’d recommend giving a collection like this a try. It sometimes pays to give the classics a second look.

Hawthorne, N. (2006). The celestial railroad, and other stories. New York: Signet Classics.

Friday Reads: The Disaster Artist, by Greg Sestero & Tom Bissell

No one would seek out a bad meal. If you heard a friend rant about an awful vacation, you wouldn’t check prices for the next flight there. But art is different: it can entertain and stimulate even when it fails to accomplish its goals. Sometimes especially when it fails. “Bad art” is not always bad—under the right conditions, it can be sublime. And if it’s entertaining, is it really bad?

No one would seek out a bad meal. If you heard a friend rant about an awful vacation, you wouldn’t check prices for the next flight there. But art is different: it can entertain and stimulate even when it fails to accomplish its goals. Sometimes especially when it fails. “Bad art” is not always bad—under the right conditions, it can be sublime. And if it’s entertaining, is it really bad?

The Room has been called “the Citizen Kane of bad movies”. Written and directed by Tommy Wiseau, a shadowy character of unknown origin, the film is essentially a tragic love triangle involving a banker, his unfaithful fiancée, and the banker’s best friend. It seems to be standard fare, but The Room delivers this routine story through a narrative that’s full of quickly-dropped disease and drug subplots, continuity errors, and astonishingly incoherent dialogue (“You don’t understand anything, man! Leave your stupid comments in your pocket!”). If aliens who had never interacted with humans tried to stage an episode of Melrose Place, it would feel like The Room. One early review described it as “like getting stabbed in the head.” Some films leave you with questions about existence, ethics, art—the first question that comes to mind after viewing The Room is “how could this happen?”

This book explains how. Some things are outlined in more detail than others, as Sestero respects Wiseau’s famous reluctance to discuss his past. In fact, the book’s strongest moments capture the friendship between Sestero and Wiseau. I was concerned that The Disaster Artist would be full of jabs at Wiseau’s hubris and that sometimes happens, but the book generally presents him as a sometimes kind and warm, if very naïve and very, very strange, person. It’s rather analogous to the Tim Burton biopic about Ed Wood in its loving treatment of an outsider. And it’s surprisingly well-written, given that it’s ostensibly a book about a baffling cult film. The narrative is split between Sestero’s real life adventures with Wiseau and a day-by-day account of the film’s production, but its back-and-forth structure never becomes confusing. Unlike The Room itself.

It’s the perfect time to see The Room and read this book, as there are two related films set to be released this year—a mockumentary starring most of the original cast and a posh studio adaptation of The Disaster Artist featuring Bryan Cranston and Sharon Stone, among others. You will probably never surpass me in terms of Room fandom (so don’t worry), but you will be ahead of the curve if 2016 turns out to be a year of Room fever. And you will also know all about the flying vampire car that didn’t make into the final version of the film. Yes, really.

In my opinion, a bad film is a boring film (oh, hi, The English Patient). The Room and its brethren (like Troll II and Dunyayi Kurtaran Adam) are endlessly entertaining and rewatchable. The Disaster Artist captures the energy and atmosphere that make these films unique. They’re surreal and special. Not bad.

Sestero, G., & Bissell, T. The disaster artist: My life inside The Room, the greatest bad movie ever made.

Friday Reads: The Circus in Winter by Cathy Day

“When I was little, my mother told me there are basically two kinds of people in the world: town people and circus people. The kind who stay are town people, and the kind who leave are circus people.”

“When I was little, my mother told me there are basically two kinds of people in the world: town people and circus people. The kind who stay are town people, and the kind who leave are circus people.”

And neither are guaranteed happiness, which these stories make crystal clear. Spanning decades and connected by both the circus and the small Indiana town in which it spends the off-season, these tales present a dazzling array of characters—elephant trainers! Zulu queens! Driveway-paving Gypsies! But this is the circus in winter, when the lights have dimmed and the canvas has dropped. It’s not focused on public spectacle, but on the often heartbreaking private lives of these extraordinary people.

Wallace Porter assembles his circus to assuage his own broken heart. Over the years, he imports transient talent from all over the globe. The circus, like the Pequod (or like the United States), becomes a “big tent” which includes people of assorted backgrounds working together for common goals. But they’re also united by human experience—death, failed relationships, and the feeling of entrapment generated by familiar surroundings. This is a somber book, but it’s not really a tearjerker in the Nicholas Sparks style. It’s muted and plaintive, even in its humor (“They cried for a while, then went downstairs to make pancakes.”).

Structurally, Day’s book is reminiscent of Winesburg, Ohio and Olive Kitteridge. Midway between a novel and set of short stories, The Circus in Winter lacks a true central narrative, but is united by overlapping characters and overarching themes. And, of course, the circus looms over all of these tales, whether as the place where the clowns live or as a symbol of escape from snowy small towns.

“A depressing book about the circus, but only the backstage stuff” is probably one of Earth’s hardest sells. But this is a compelling work that deserves a wider audience and is perfect for bleak winter days.

Day, C. (2005). The circus in winter. Orlando: Harcourt.

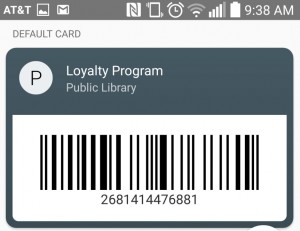

Tech Tuesday: Mobile Pay

All too often, technology seems disruptive and stress-inducing, especially to libraries that are already providing a full range of popular services. It’s one more thing to worry about! But, ideally, tech can augment those services and make life easier for people on both sides of the circulation desk. To give you an example, let’s talk about fines.

Fines are not extremely exciting. No one would rush to read a special “Fines Issue” of Library Journal and no one includes fines in her sentimental thoughts about libraries. But fines are commonplace in most public libraries and technology, in the form of mobile payment, can make them easier to handle.

Mobile payment (or digital wallet) platforms allow users to pay for purchases (or fines!) by using their portable electronic devices. It works through the use of NFC (near field communication) terminals. An app on the phone or smart watch is linked to a bank or credit card account. At a point of service, the device is unlocked, the user authenticates the purchase, and the app transmits payment information to the terminal. The exchange is completed without ever touching cash or a card. You don’t have to worry about uncrumpling a crumpled wad of bills or wrapping a buggy credit card in a plastic bag.

Beyond those material benefits, mobile payment also plays to the library’s traditional concerns with privacy. Most apps assign a substitute card number to the device, so the NFC terminal never receives a user’s real card or account number. With hacks becoming a more frequent concern, this ensures that actual card and account information is less vulnerable to compromise.

You’re likely to be seeing NFC terminals in more places, as they’re frequently included with the new chip-card readers that are replacing older magnetic-stripe readers. The current major players in mobile payments—Apple Pay, Android Pay, and Samsung Pay—all use NFC technology, although it should be noted that some of the newer entrants are opting to use QR codes for their financial transactions. According to one estimate, money spent through these sorts of transactions will increase from $4 billion in 2014 to $34 billion in 2019. Needless to say, all signs point to years of growth for mobile pay.

But there’s potential for more than just payment here. My Android Pay app allows me to store my library card number (which it amusingly classifies as a “loyalty card”). If my library allows it, I can then use my phone to get my books at the circ desk or self-checkout. That means one fewer card in the wallet or one fewer tag on the keyring! Additionally, the app has a feature which will alert me when I can use the card at a nearby location. It’s strictly theoretical at the moment, but a feature like this could be a boon to libraries that are offering service outside their brick-and-mortar buildings. It could help direct passers-by to a mobile makerlab or a self-service kiosk, and it’s an option that is likely to be enhanced as libraries broaden support for mobile pay apps.

Mobile pay has the potential to make library life easier without a tremendous amount of strain. It’s a great example of technology that can easily integrate into and improve existing library operations.

Posted in Technology

Leave a comment

Live Streaming

Libraries connect people with information and technology is constantly providing us with new ways to reach our communities. Streaming—the broadcast of live video, generally from the camera on a smartphone or mobile device—promises to be a great way to share programming and wow our users with new resources. Streaming probably won’t be the centerpiece of your communication strategy, but it does have appeal as a sporadic tool for special events. The number of choices available for platforms, the ease of use, and the excitement of live broadcasts all mean that it might be a great fit for your library.

Facebook is everywhere—even the most small-scale libraries ordinarily have some sort of Facebook presence. This might make it the ideal entry point for libraries looking to dive into streaming. Facebook is currently providing its streaming feature, Live Video, to a small number of iPhone users in the U.S. It’s integrated into Facebook’s existing architecture—to start streaming, you’ll tap Update Status, then select the Live Video icon. As with other status options, you can restrict which audience will see your stream. During the broadcast, you’ll be shown a real-time feed of comments from your viewers. Once you’ve finished, your stream will be saved on your timeline like any other video and available for your visitors to replay.

Facebook streaming will eventually be rolled out to more users, but, in the meantime, you might consider other alternatives to get some streaming practice. The current Big Two of streaming are Periscope and Meerkat. Periscope is owned by Twitter and available for iOS and Android devices. Its audience is pretty impressive: every day, its users are viewing not just hours, but nearly 40 years of video (just over 350,000 hours of video streamed per day). It remains to be seen how Facebook streaming will affect those numbers, but for now Periscope offers an established platform that attracts a lot of eyes. Broadcasters have plenty of options for their streams—video can be available to the public or accessible only to a selected audience. Individual viewers can be blocked, so you won’t have to worry about rowdies wrecking your broadcast. Broadcasts (or “scopes”) disappear after 24 hours, although users can capture their scopes using resources like Katch. The Salt Lake City Public Library and Minnesota’s Hennepin County Library are among the profession’s Periscope enthusiasts. To see what’s possible with the platform, you might browse some of the archived videos on Katch—this brief scope gives viewers a taste of a library’s makerfaire, for instance. There’s also a new Facebook group devoted to Periscope in libraries that can provide some possible ideas.

Meerkat offers apps for iOS and Android. Once users have signed up, they can connect their Meerkat accounts to Facebook. This allows direct streaming to their followers as soon as they begin broadcasting and also permits the use of Meerkat’s Cameo feature. Cameo permits broadcasters to share control of their stream, giving invitees one minute of screen time and alerting his or her Facebook friends about the stream. Another Meerkat-specific feature is the end-of-broadcast button, which can direct your viewers to a particular site after the stream has ended. As with Periscope, Meerkat users can archive their streams with services like Katch. This BBC article on the Ferguson protests has tons of information about the benefits and challenges of the platform (although you should be aware that Meerkat no longer has direct connection with Twitter feeds).

There are, of course, other options for streaming beyond the Big Two. Ustream and Livestream were early entrants into the world of streaming and both are still strong contenders. For those who might be more comfortable with familiar names, YouTube also offers live streaming. Undoubtedly, new services will emerge as streaming becomes more and more popular. The right platform for your library depends, of course, on your needs. Features, cost, learning curve, and archiving options are all important considerations.

Streaming lets you show the world what’s happening at your library. It puts eyes on your programming, even outside the building, or allows you to give your users a sneak preview of new resources or remodeled areas. But it can also help to bring experiences from the wider world into your library. Why not follow up a travel program with a live broadcast from the place that was discussed or plan an author talk via Meerkat or Periscope? Streaming gives us powerful tools to widen our reach and create new connections between the library and its users.

Posted in Technology

Leave a comment

Virtual Reality

Virtual reality has been a hot topic for a long while, but only recently has the technology reached levels of price and accessibility that have made it worth considering for non-gigantic libraries. The phrase “virtual reality” brings to mind clunky glasses strapped to the face and, make no mistake, fully wearable hardware is still a huge part of the virtual reality landscape. Microsoft’s upcoming HoloLens and Oculus Rift’s new headset are good examples of fully-prefabricated VR devices that you affix to your head. They’re also good examples of pretty expensive technology, outside the budget of libraries which are not already committed to large-scale VR projects. But there are affordable alternatives for those who are interested in trying out VR without breaking the bank.

It doesn’t get much more economical than Google’s Cardboard project. Google offers downloadable instructions which will allow you to make your own VR viewer using magnets, Velcro, and cardboard from an old cereal or pizza box. If you’re not inclined to DIY, you can also purchase pre-assembled cardboard or plastic viewers from a vendor. Once you’ve built or bought your Cardboard set, you’ll insert a fairly new and large smartphone into the viewer.

Other manufacturers offer similar budget-friendly tech. Oculus is offering a $99 headset which works with 2015 Samsung phones. Even View-Master has revamped their product into a $30 virtual reality device. Don’t worry, they still use reels. There are plenty of other companies which provide low-cost VR viewers. Potential buyers should remember, however, that many of these devices work in tandem with smartphones, so be sure to budget for both the $30 Google Cardboard set and the $600 cell phone.

So what can you do with this technology? As you might expect, games are a natural fit for virtual reality. The popular game Minecraft is coming for the Oculus Rift and Google’s Play Store has an entire section devoted to VR-friendly apps for Cardboard. But the possibilities extend beyond gaming. The recent Democratic debate on CNN featured a virtual reality broadcast that was apparently rather quirky. And some hotel chains are experimenting with VR devices that allow viewers to travel to far-flung locations. Imagine a program on weather that would allow patrons to step into a hurricane through a VR viewer. Or a program on Italian cooking that ends with a VR tour of Milan. With costs dropping, it’s becoming affordable to experiment, so you might consider finding a place for virtual reality at your library.

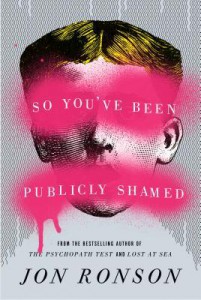

Friday Reads: So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed

In history’s darker days, ne’er-do-wells were marched to public squares, sometimes by mobs waving torches or pitchforks, and displayed publicly as punishment. Here in 2015, most of us don’t have pitchforks or torches at home. But almost all of us have Facebook or Twitter or Reddit accounts. We also have the same basic impulses that drove extrajudicial justice in the past.

In history’s darker days, ne’er-do-wells were marched to public squares, sometimes by mobs waving torches or pitchforks, and displayed publicly as punishment. Here in 2015, most of us don’t have pitchforks or torches at home. But almost all of us have Facebook or Twitter or Reddit accounts. We also have the same basic impulses that drove extrajudicial justice in the past.

This is where Jon Ronson’s latest book begins. Times and tools have changed, but people haven’t. Some people still exhibit offensive (if not really criminal) behavior—plagiarism, insensitive jokes, outright lying. And some other people don’t like it and aren’t afraid to use the tools at hand to do something about it.

It’s probably never been fun to be publicly shamed. But, in the past, you’d eventually stop riding the rail, or go home and wash the tar and feathers off. At worst, you could move to a different village. Public shaming on the Internet has a bit more permanence. How do you ever move forward with your life when your bad deed has been retweeted thousands of times? How do you get a new job when that employer Googles your name and sees very cringeworthy images?

This book answers these questions and (re)introduces the reader to some famously shamed people. Those who have read Ronson’s The Psychopath Test and exquisite Them: Adventures with Extremists will recognize his narrative multitasking and brisk style. For a book with such substance, this is an exceptionally quick read—you can finish it in an afternoon—and it’s worth your time. The anonymous “mob justice” aspect of the Internet, which sometimes gets things extremely wrong, continues to grow anyway (and probably won’t be limited to shaming only the worst offenders). This book is all about that behavior and might make you rethink your next Send, Like, or Share.