The most profound technologies are those that disappear. They weave themselves into the fabric of everyday life until they are indistinguishable from it.

Mark Weiser

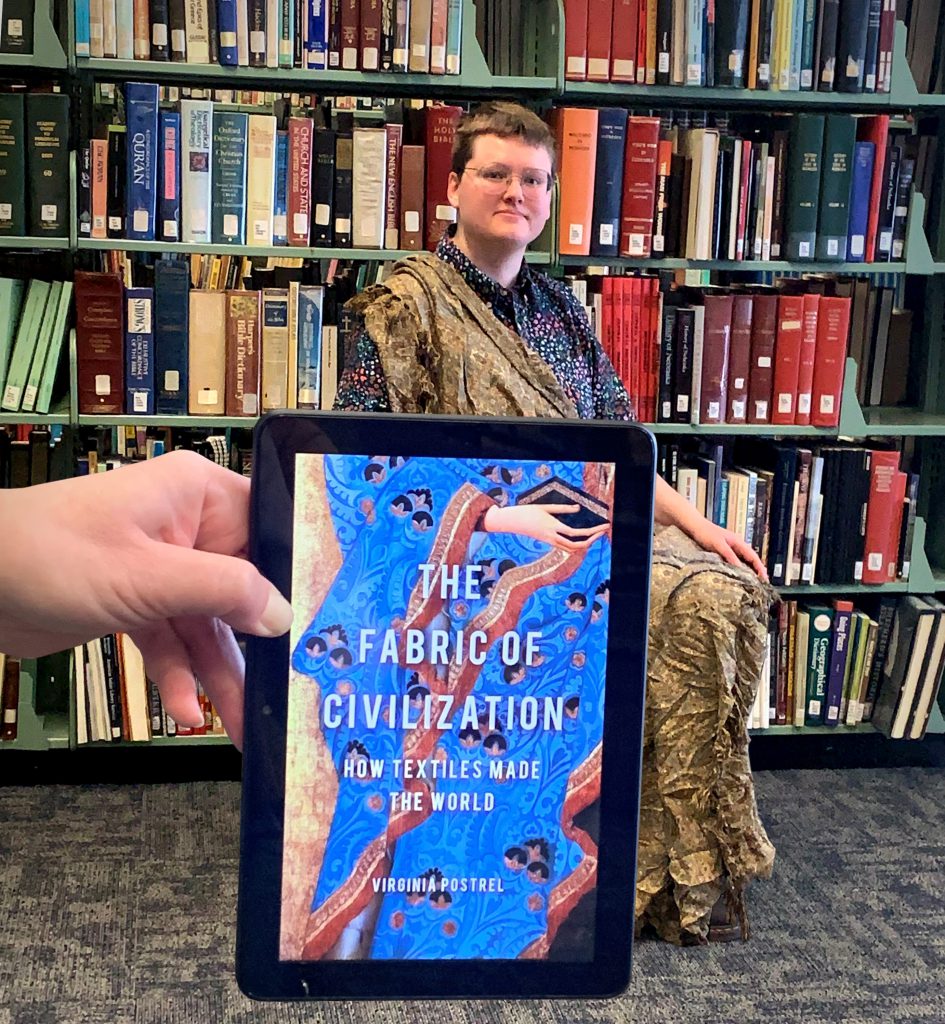

Virginia Postrel’s The Fabric of Civilization begins with the dawn of human history, with the first fibers twisted into string, and ends with modern innovators creating new fibers and types of fabrics. The book is sectioned into seven chapters, each covering a certain step in the fiber-to-textile life cycle: Fiber, Thread, Cloth, Dye, Traders, Consumers, and Innovators. Postrel’s core thesis: fabric was among our first technologies, and it was also our most crucial and defining technology — and it still is. “We hairless apes co-evolved with our cloth,” Postrel writes. “From the moment we’re wrapped in a blanket at birth, we are surrounded by textiles.”

This book was absolutely fascinating. As a knitter, crocheter, and now a beginning spinner, part of my awe for the fiber crafts comes from their long-stretching history: from me, to my grandmother, to endless generations past. The way I spin yarn from wool, sitting on my couch in front of the TV in 2024, uses the same motions that would be familiar to someone in ancient history. Fibers spun into thread were necessary for the cloth needed for sails, clothing, blankets, political functions, military uniforms, and religious/cultural rituals. My burgeoning love of spinning is likely why Chapter 2: Thread was my favorite. Postrel’s breakdown of how long it would take spinners and their spindles from different eras to produce the thread that was so crucial for exploration, competition, commerce, and general livelihood was incredibly thorough. Take a moment to think about all the fabric around you right now. That fabric is composed of woven threads or knitted yarns. Today’s modern factories use heavy machinery to spin fibers into miles and miles of that thread for jeans, cotton shirts, and wool coats. For much of history, however, that process needed to be done entirely by hand. Much of the rest of the world’s economy could not work until the spinners did, and the quest to expedite the process drove inventions and innovations that had far-reaching effects on industries beyond that of textiles.

At times, Postrel’s overview and analysis bottlenecks into myopia, and the occasional – but thankfully brief – insertions of her own personal experiences with the textile process were jarring. Postrel occasionally falls into a columnist’s cadence, sacrificing the distance of academic de rigueur for a more conversational tone. Another reader might appreciate the first-person connections and exposé-esque sections – a la How It’s Made – and I can certainly understand the reasoning behind her choice, but I did not find that these added much to the book.

Her myopia, however, is less forgivable. Postrel would have crafted a more solid body of work had she matched the title with the true scope of her endeavor, and called the book The Fabric of Western Civilization. Industrial Revolution-era Europe and New England are centered far more prominently than I would have preferred. Postrel touches briefly on the interaction between the South’s cotton industry and England’s mills — even after the latter abolished slavery — but doesn’t spend as long on that connection, even though I feel it would have bolstered her argument about global commerce and economy. This was an especially disappointing flaw, especially given Postrel’s own definitions of “civilization,” including the fact that it is a cumulative process not bound to one region or culture; in fact, as Postrel does mention, exchange (willing and unwilling) is what drove the evolution of textiles and humanity both.

Postrel also falls into the trap of rebuttal for the sake of novel arguments, which end up bordering on dismissal of broader historical truths: particularly and most egregiously in her argument about cotton in the Pre-Civil War South, singling out Edward E. Baptist’s The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism (2013) and his statement that increased cotton production was caused by ever-intensifying brutality inflicted on enslaved people. Postrel counters that the production increase can be simply explained, instead, by advancements in both cotton stock and processing technologies. However, there is no reason why both cannot be true. The same root issue is also at play when she disregards the low-wages of the pre-industrial (and typically female) spinners as solely a business decision, devoid of the influence of gender and class politics. History is not a field with single-causes and single-effects.

Part of the appeal of non-fiction to me, however, is actively engaging with the arguments that the author presents. A sense of wonder is important, but I also want to think about the topic and build my own perspective. And so, overall, I enjoyed the book. I listened to the audiobook read by Caroline Cole, but I do plan to check out the print copy from my local library, in order to explore Postrel’s footnotes and bibliography for further reading and learning opportunities.

You can find “The Fabric of Civilization: How Textiles Made the World” by Virginia Postrel is available for download on BARD, the Braille and Audio Reading Download service. BARD is a service offered by the Nebraska Library Commission Talking Book and Braille Service and the National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled at the Library of Congress.

Love this #BookFace & reading? We suggest checking out all the titles available in our Book Club collection, permanent collection, and Nebraska OverDrive Libraries. Check out our past #BookFaceFriday photos on the Nebraska Library Commission’s Facebook page!

Postrel, Virginia. The Fabric of Civilization: How Textiles Made the World. Basic Books/OrangeSky Audio, 2021.