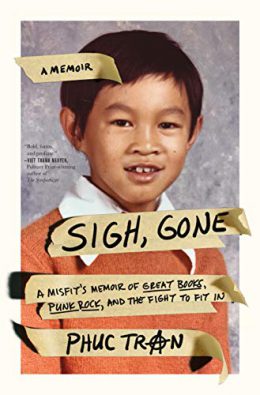

I love memoirs. Not only do they offer readers insight into what it’s like to live lives different from their own, they also remind us of how much we humans have in common. That’s definitely the case with Sigh, Gone: A Misfit’s Memoir of Great Books, Punk Rock, and the Fight to Fit In, by Vietnamese American teacher, writer, and tattoo artist Phuc Tran.

In 1975, when Tran was one, his family fled the fall of Saigon and wound up resettled in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. In Sigh Gone, Tran describes what it was like growing up as a member of “the token refugee family” (2) in town. As one can imagine, it included schoolyard taunts and name-calling, and, when out in public with his family, the discomfort of always sticking out.

Tran also describes the resentment he felt toward his parents over what he saw, at the time, as their cultural and English language failings: “I needed to trust in my dad’s ability to navigate the world at large, and I was already doubting him. . . . Five-year-olds were supposed to believe what their parents said. Maybe some kids’ parents still had the golden nimbus of infallibility, but not my parents and not for me” (16).

Going forward, Tran chronicles his relentless efforts to assimilate. By high school, his two-pronged strategy included pursuit of academic excellence and successful integration into the punk/skater subculture. Of the later, he writes, “[b]eing a freak because of my weird clothes and hair was a respite. These were things that I had chosen . . . Fighting rednecks because you were a punk was far better than fighting because you were Asian, and fighting with allies was far better than fighting alone” (6).

So why did this book resonate with me? For one, Tran’s depiction of high school, with its cliques and angst—a “cultural cul-de-sac built with the craftsman blueprint of John Hughes, the Frank Lloyd Wright of teen malaise” (2)—is viscerally familiar. His description of his job as a library page also warmed my librarian’s heart, as did his discovery and adoption of Clifton Fadiman’s The Lifetime Reading Plan, which he stumbled on while prepping for the library’s used book sale.

Though the Plan, was “unapologetically American, classist, and white” (4), Tran could not have cared less at the time; it served as a catalyst for his burgeoning love of literature–which the English major in me appreciated. He also viewed the Plan as his entrée to the world of big ideas that can connect people across time, geography, and culture—which is what Tran, himself, has accomplished with this memoir. Sigh, Gone concludes right after Tran graduates from high school, just as he’s poised to head off to Bard College, which had described itself to him in its admissions literature as “A Place to Think” (267). So fitting!