Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty of UK band, The KLF, reunited for 23 minutes at 00:23 on August 23, 2017 (8+2+3+2+0+1+7=23) for one final show. It had been 23 years since their last performance.

In 1995 they had written up a contract banning them from discussing their band (The KLF), their art foundation (the K Foundation), or the unbelievable act they committed the year prior, for 23 years. The contract, written on the top of a ‘68 junker named Ford Timelord, was then pushed off a cliff. By this point, they had already deleted their entire back catalogue of music.

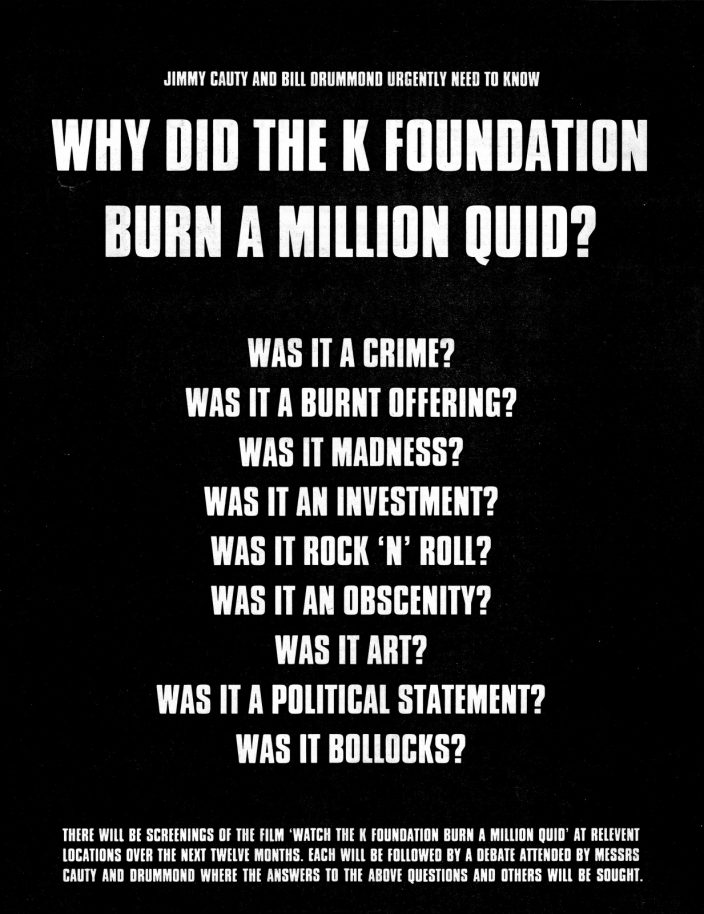

The year before, they had taken one million pounds of cash they made from topping UK charts to a Scottish island with a single press witness who recorded the event and they burned it all up. It was even verified by their bank.

They made it a movie and screened it all over the UK. After each show, they would invite the audience to debate why they burned it all and what it meant.

The public wrote them off as assholes. Not only had they burned an insane amount that most of us will never get close to, but they couldn’t even say why they did it.

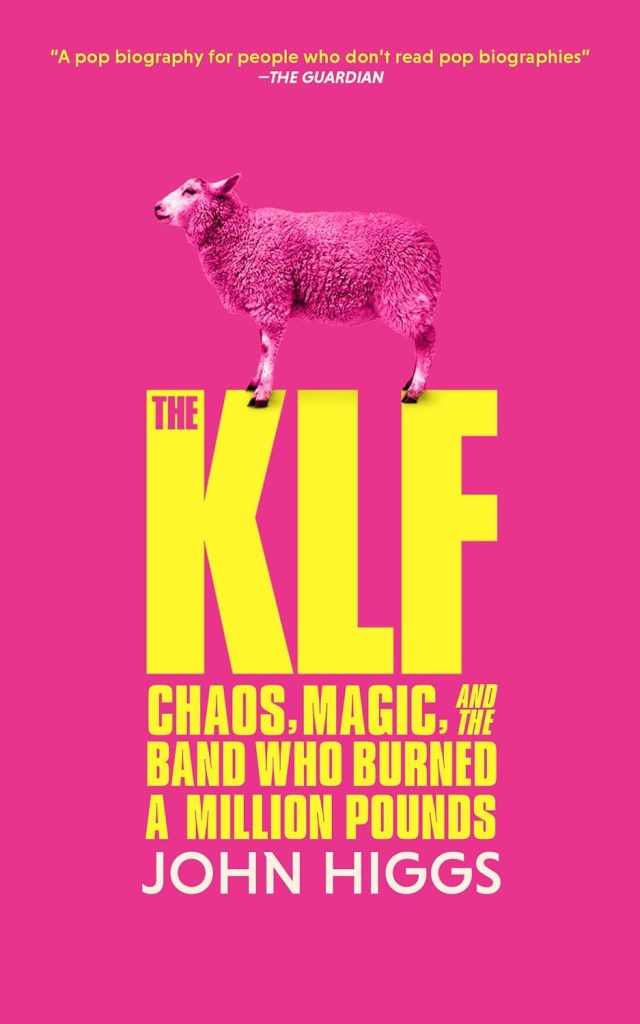

Music Historian John Higgs returns to the question in his book, The KLF: Chaos, Magic, and the Band Who Burned a Million Pounds, to place it in a new context—magic.

To explain this, Higgs repeatedly turns to Alan Moore, friend of Drummond and creator of V for Vendetta and Watchmen. Moore speaks on a version of collective unconscious that he calls Ideaspace—a vast universe of ideas, invisible, but accessible to all of us. It includes the private and public, real and unreal, known and unknown; an endless place where ideas can be entire continents. It’s an ether of creativity, emotion and, in the furthest corners, madness. It does not exist but it creates. This is the magic.

I’m paraphrasing, but Higgs clarifies the path to arrival at this point: “As everyone from magicians like Moore to the most rational scientist will tell you, magic is only in the mind. But this, of course, is also the realm of art—it’s the role of art to explore and illuminate and express this very territory” (167).

Higgs traces The KLF’s journey into outer Ideaspace, moving farther and farther away from the busy main street of regular, everyday, easily digestible ideas. The spectacles they brought out of Ideaspace reflected this: they wore horns on their heads, performed fake pagan rituals, dressed as ice cream cones on Top of the Pops, they left a dead sheep at an award show after party.

Basically, this isn’t Harry Potter.

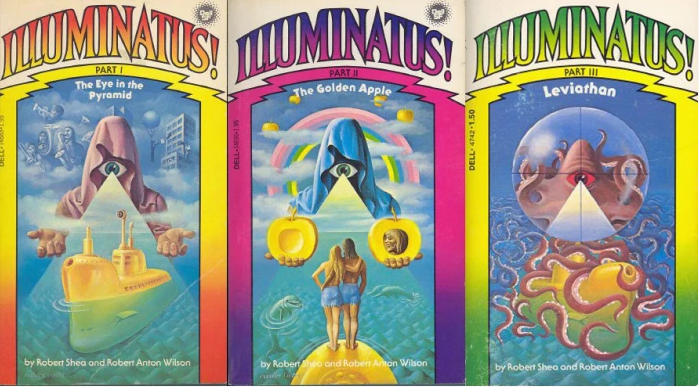

However, there is a work of fiction referenced throughout as well. The Illuminatus! trilogy by Robert Anton Wilson and Robert Shea was a sci-fi cult classic wrapped in discordianism, a 1960s neo-religion based in chaos and postmodern uncertainty.

The KLF’s first band name, The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu, was taken straight from the trilogy, and Drummond and Cauty made many references both to the trilogy, like their use of the 23 enigma. By tracing these connections, Higgs elucidates the ideas behind their crazy persona. Crazy, but meaningful to them; as Drummond put it, “there is humor in what we do, and in the records, but I really hate it when people go on about us being ‘schemers’ and ‘scammers.’ We do all this stuff from the very depths of our soul and people make out its some sort of game. It depresses me” (147).

Perhaps the money burning marks their point of no return into their ideas. Perhaps it was an attempt to break out of their spectacle and find deeper connection. Perhaps it was a ritual. Higgs doesn’t come to a solid conclusion, fittingly, but his reframing is thoughtful and so, so fun. Grab this copy from the Polley Music library, it is updated edition that includes their 2017 reunion. Their music has started reappearing online, too, while you’re at it.

Higgs, John. The KLF: Chaos, Magic, and the Band Who Burned a Million Pounds. 2012. Blackstone Publishing, 2024.